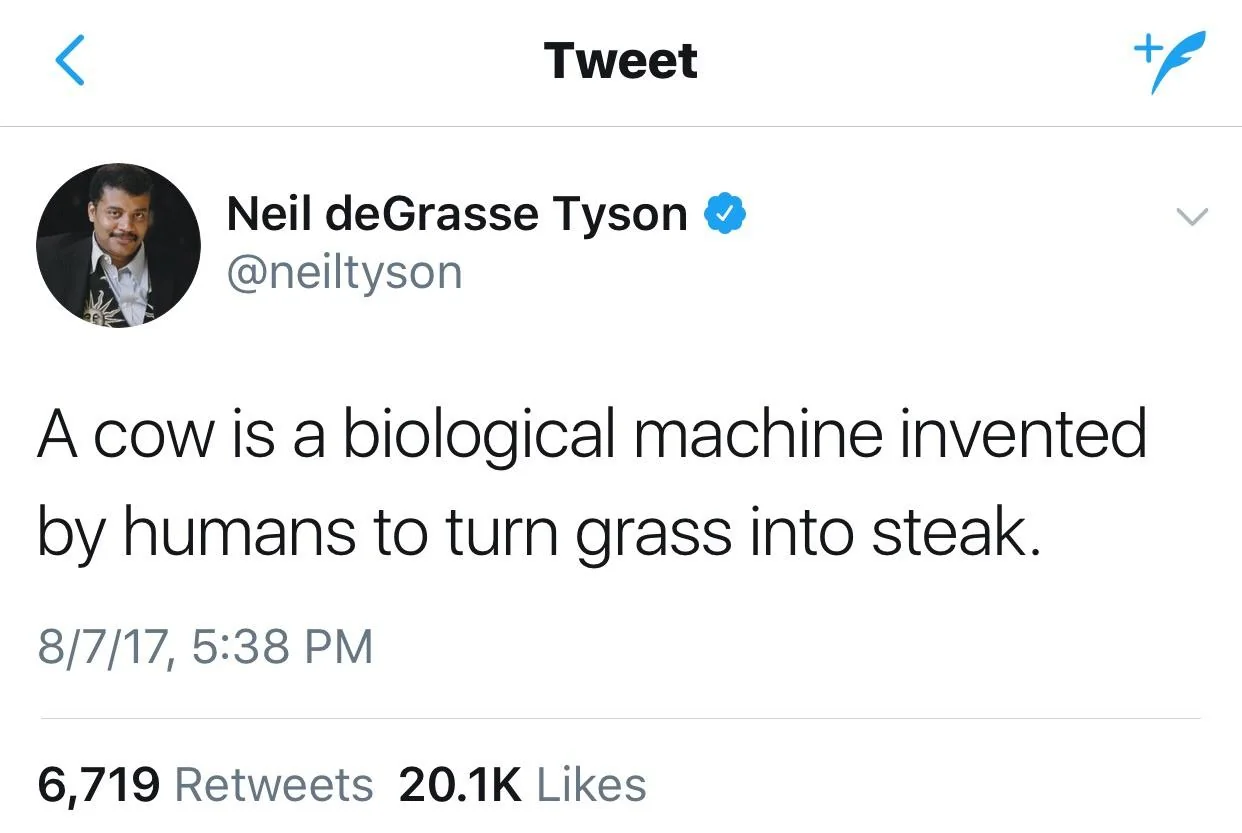

This essay starts with an extremely careless tweet from a very smart person

The most obvious critique is that we did not create the cow from nothing. We molded a conscious being from another animal—the aurochs—over the course of some 8000 years or whatever. We repurposed it, but a lot remains from the before times. The cattle still have desires and still have feelings given to them by their evolutionary heritage. They care about their young ones. They want community such as theirs is. They maybe even want freedom; they do break out sometimes. I don’t know the extent of it. We can’t really know, because the cow can’t tell us.

But I think the proper critique goes further. What if we had created the cow from whole cloth and it did experience what we subject it to? The cow has no power over us. We are far more powerful than the cow. A single person could kill millions of cows and only rarely will cows kill people. The power differential is insane. There are no situations wherein the cow can avenge their experience.

Given the power imbalance, this situation seems outside the bounds of the normal types of morality that we are used to thinking about. These moralities mostly have to do with actions towards and from our approximate equals. Don’t lie, don’t cheat, don’t steal, don’t kill, be polite, don’t slander. Basically prohibitions on the things that if you do them you corrode the very social ties that make society possible.

Then there are the moralities to with cleanliness and so on, wash your hands before you eat, don’t litter etc. Very helpful not getting you or your friends killed by disease.

I do think that those are at the core of human morality, but I think there is more. I also think there is the morality of the extremely powerful. A striking example I can think of is the Indian Emperor Ashoka who suddenly stopped a brutal and effective expansionist policy after the slaughter of about 300 000 by his army. There was nothing stopping him other than his own unwillingness to cause further bloodshed. It strikes me as a good choice for him to make, given that the incentives were mostly in the other direction. It is a sort of morality for the gods. When it is not negative consequences for the self, but a self conception that one judges ones self against that determines the rightness of the action. This is the sort of morality I think applies to us and our agricultural animals.

Luckily, we have a—somewhat limited by perspective that it is—tradition of morality for the gods to draw from. These are called theodicies. They offer a fairly relevant perspective in this case.

A theodicy is basically an attempt to answer the paradox pointed by Epicurus who is said to have said:

God, either wants to eliminate bad things and cannot, or can but does not want to, or neither wishes to nor can, or both wants to and can. If he wants to and cannot, then he is weak and this does not apply to god. If he can but does not want to, then he is spiteful which is equally foreign to god’s nature. If he neither wants to nor can, he is both weak and spiteful, and so not a god. If he wants to and can, which is the only thing fitting for a god, where then do bad things come from? Or why does he not eliminate them?

There are plenty of theodicies that we can get into and I think they will help hammer the point home, but for right now we can think about how it begins to apply to us too, albeit somewhat loosely because we are not all powerful and some of us would not claim to be good or desire to be good.

So what kind of answer do we give the cow? This animal who we had a hand in creating. Cattle are perhaps a less ideal example because they are more efficient for the amount of suffering we are causing a conscious being compared to others for the amount of protein output we get from them. For example, basically four people are fed per chicken. 10 months of torturous conditions for the chicken in which they do not have the freedom to act the way that they would if they could choose. They are subjected to quarters and crowding that are unhealthy for them and which cause decimations. Even cattle though, the dairy industry is already industrialized in America and is becoming more so in Canada. Feed lots for beef cattle are crowded, restrictive and unsanitary.

So those are the evil conditions. We have the power to stop them, or at least reduce them by reducing our own consumption. Or maybe it is justifiable by the logic of one of history’s great theodicies. Let’s try a few.

Leibniz claimed that this is the best of all possible worlds. I don’t think we could claim that for ourselves. We could easily reduce the suffering we inflict on these animals. We don’t need to have meat grown on a farm. We would be just fine—we would be healthier in fact—if we didn’t.

How about the Brothers Karamazov or to some extent Augustine’s? Rebellion. God created the space for something different from him and it rebelled and that is the source of suffering in the world. I have trouble believing that about domestic animals. It’s not their rebellion that causes their suffering. It’s not them being wicked, though perhaps sometimes they are anti-social and that does cause some suffering, but I would say they are so in fairly predictable ways and we could alleviate that. As far as creating something separate from ourselves that is not necessarily good because we are good, I’m not sure it even makes sense.

There is Hick’s view that it is preparatory. We live in a world that teaches us things through suffering—and that is true of our world—but that crucially depends on an afterlife. I don’t know what kind of afterlife you ascribe to animals. I am prone to think that their souls are destroyed with their bodies. It’s up to you. If you think there is some cow heaven the suffering that we have caused them will be meaningful, maybe. Though one large difference regardless of your view is that we are not doing this for their benefit.

There’s the Howard-Snyder theodicy which I find fairly interesting. It works almost as an opposite to Leibniz’s: is it possible to create an unsurpassable world? They would argue no by virtue of God’s omnipotence, he could alway create a better world than any world imaginable. Lets look at it from a crudely utilitarian perspective: say you have a paradise of 50 people, you could easily create a paradise with 500 people and so on and so forth if you are an all powerful being. In fact, it is the all powerfullness that prevents him from creating the best of all possible worlds. They go on to argue that just because he cannot do that, that does not mean that God is not himself good. God can create a world whereof a better one could be created or imagined as long as he views it as worth creating. I think we as the creations hope for it to mean that he considered our experience before doing it. This is perhaps the most applicable. Even for our level of power, we can always do better, so this one may apply to us. I would argue though that we have a situation wherein we created a thing without considering it at all and now that we have it, we should at least consider it from our creation’s perspective.

That’s the core of it. There is this huge power differential and a matching indifference that I can’t help but think that we would condemn God for were the shoe on the other foot.

So, I mean this whole theodicy argument. I don’t expect it to compel anyone. I just expect it to shut a door you may try to exit out of if you don’t find this compelling Bentham’s old line on the circle of moral concern:

the question is not whether it reasons, it’s does it suffer

Maybe this a trivial insight, but when I heard it in ethics class it felt like lightning. We all have experience of suffering. We all know at least to some extent what we are inflicting on these beings and we have to ask ourselves why is it good for me to have somewhat more pleasure eating supper at the expense of a horrible bleak existence for these animals, but if you don’t find that compelling I at least ask you think about how you would defend your actions toward the cow from the view of a god.